|

Slums are headline news — again. From Stewart Brand’s über-optimistic take in his book Whole Earth Discipline to the murk and violence of Slumdog Millionaire, slums are portrayed alternately as miracles of innovation and the ultimate trainwreck. Barbara Kiser finds the truth lies somewhere between.

The quiet revolution unfolding in one of Asia’s biggest informal settlements reveals a rare but replicable dynamic. With little more than sewage pipes, microfinance and communal will, the poor — together with a dedicated band of on-site technicians and visionaries — have transformed their world. The quiet revolution unfolding in one of Asia’s biggest informal settlements reveals a rare but replicable dynamic. With little more than sewage pipes, microfinance and communal will, the poor — together with a dedicated band of on-site technicians and visionaries — have transformed their world.

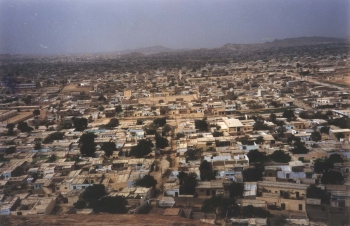

Karachi is a city caught halfway between vibrancy and dereliction. Over 15 million people throng the streets, juice bars and spicy biryani joints of this ‘mini-Pakistan’, so called because it’s the only place in the country where all six major languages are spoken. This fast-growing megacity is Pakistan’s commercial centre and sole international port, harbouring half of the country’s business and industry and 10 per cent of its population.

But behind the clamour and smoke, the barrage of ancient buses and the pungent odours mixing on the breeze — all the vital signs of a living, breathing metropolis — lies another layer of reality. Over 60 per cent of Karachiites live in katchi abadis, informal settlements where the vast majority must survive below the poverty line — and with the daily fear of bulldozers round the corner. Since the early 1990s a number of government agencies and developers, backed by police and paramilitaries, have demolished vast swathes of these slums and shantytowns, displacing nearly 190,000 people.

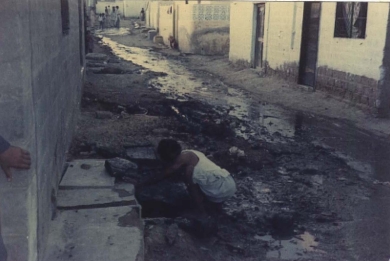

Karachi’s frenetic commercial activity and unchecked growth have meanwhile created a raft of environmental problems. Unregulated, untreated industrial effluent, farm runoff and sewage have fouled waterways, the port, and the city’s mangrove-studded coast. Ill-planned, expensive housing built along coastal outfalls has led to flooding in the city after heavy rains. Many katchi abadis lack ‘joined-up’ sanitation systems, and raw sewage ends up coursing down their lanes, bringing disease in its wake.

Conduit for change

It takes genius to knock two challenges of this magnitude together and come up with a solution. But this is exactly what happened back in 1980, when Akhtar Hameed Khan came to Orangi — a million-strong katchi abadi at the city’s edge.

Like many others, Orangi was awash with problems such as inadequate water and sanitation, and significant levels of childhood illness and mortality. Khan was unfazed. A pioneering social scientist, he was bent on finding a way to get Orangi’s communities moving on the issues themselves with some judiciously selected training and support. His intent was to use the findings to create replicable models. Like many others, Orangi was awash with problems such as inadequate water and sanitation, and significant levels of childhood illness and mortality. Khan was unfazed. A pioneering social scientist, he was bent on finding a way to get Orangi’s communities moving on the issues themselves with some judiciously selected training and support. His intent was to use the findings to create replicable models.

Working with Agha Hasan Abedi, chairman of Pakistani charity BCCI (the Bank of Commerce and Credit International Foundation, now known as the Infaq Foundation), Khan identified the four key issues Orangi needed to tackle – sanitation, health, education and employment.

Khan started with the basics: sanitation. Calling the venture the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP), he recruited local activists. He began talking to people and walking the lanes — many, at that point, little more than open drains swimming with waste water and human faeces.

A proper underground sewerage system was clearly needed. But while a number of residents were calling for foreign loans, Khan viewed international debt as a poverty indicator. He saw, too, that outside funding was unaffordable for all sorts of reasons, from high overheads to profiteering by contractors and consultants’ fees.

So he took a radical step. He asked the poor to finance their own transformation.

Streets ahead

As a backup, Khan and his fledgling band established a technical unit in the OPP. A local engineer, draftsman and plumber were brought in. Tools and instruments were provided. A neighbourhood organisation was formed in each lane to liaise with OPP technicians and handle funding.

The first 20 families then began paying for and laying their own sewerage systems. Per household, the cost for an interior latrine, the main drain in the lane and a secondary collector drain was a few dollars — and is still just US$25 today.

The revolution progressed lane by lane. Piped and paved over, they were finally clean. Disease abated and infant mortality rates plummeted. And gradually, as the confidence and skills of the people grew, they were able to build better housing, schools and clinics.

A generation knowledgeable about drafting, engineering, surveying, architecture and community organisation emerged, and a number of young people took up these professions. Some of them, in turn, fed their talent and experience back into the community.

By 1988, the OPP had diversified. Its research and training institute (OPP-RTI) handled sanitation, housing, education, training, research, advocacy and documentation, and there was a charitable trust operating a microcredit programme for small enterprises, a health and family planning programme and a foundation for rural development.

By 1995, over three quarters of Orangi’s households had proper sanitation. The next two decades would see the OPP roaring ahead.

Architect of hope

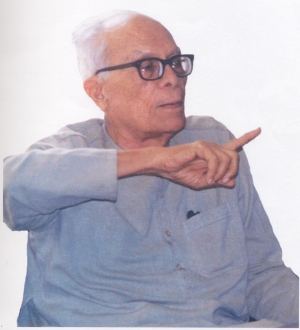

Much of Orangi’s success is down to the fact that it’s a finely tuned collaboration between the people and OPP. Khan’s shaping influence is still keenly felt, and the institute is a magnet for people with vision. One of them is Arif Hasan.

Hasan, a Karachi architect, became involved with the OPP in 1981, when Khan asked him to advise on technical aspects of sewerage system construction. Hasan became principal consultant to the project and came up with a number of innovative solutions tailored to local demand, such as cheap steel manhole covers cast in situ, sensible tools and simple rules of thumb for determining gradients.

While working as a conventional architect in the 1960s, Hasan had woken up to injustices in the ‘other’ Karachi when old friends from the poor neighbourhood where he had grown up came to visit.

At that time, as now, there were mass evictions of the poor and redevelopment driven by corporate muscle. The rawness, diversity and ad hoc inventiveness of the katchi abadis failed to fit the Western-style notions of ‘modernity’ that were increasingly attractive to local and national government. By the time Hasan met Khan and Abedi, he was well aware of the injustices — and ready to act.

Hasan has now been at the OPP-RTI for more than two decades, taking over the chairmanship after Khan’s death in 1999. Consultant to a range of international agencies and NGOs, he now also chairs Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre, works with the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a member of the UN Advisory Group on Forced Evictions.

It’s a career based on the long view. Says Hasan: “It began with a lane in 1980. It has spread all over Pakistan today and is increasingly influencing government policies related to water, sanitation and land.

“A whole new generation has developed to own and direct the project.’

Solid legacy

The OPP legacy is proof that close, on-the-ground collaboration on development can trump government ‘hit and run’ funding. For US$1.76 million — roughly a fifth of the cost of a state programme — the residents of Orangi have installed 6,700 lane sewers, over 500 secondary sewers and more than 100,000 latrines. This formerly marginalised, chaotic settlement is now a thriving mix of working- and middle-class families with over 1000 schools and clinics.

The news has spread, and to date nearly 60,000 houses in 44 settlements in Karachi, and 22 Pakistani towns, have benefited from OPP-RTI expertise. Karachi’s municipal water and sewage board has accepted the OPP-RTI’s proposal for a locally resourced city sewage system. The news has spread, and to date nearly 60,000 houses in 44 settlements in Karachi, and 22 Pakistani towns, have benefited from OPP-RTI expertise. Karachi’s municipal water and sewage board has accepted the OPP-RTI’s proposal for a locally resourced city sewage system.

The OPP sanitation model has affected policies and projects at all levels of government and in international agencies, universities and NGOs. Across other borders, poor communities in Central Asia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and South Africa are now replicating the programme, with advice and training from the Karachi ‘mothership’.

There’s no mystery to this success. Orangi works because the OPP approach is genuinely ‘bottom up’. Local communities will inevitably be more concerned and knowledgeable about their own living conditions than a newly arrived rep from a faceless foreign agency. If neighbourhoods then take on the needed changes themselves — whether that’s tree planting or sanitary pipe-laying — they will own both process and outcome. The fit with local needs will be seamless, the results positive, and the motivation to maintain and build on improvements will be strong.

Pragmatic to the bone and firmly rooted in local realities, the OPP remains a rare inspiration in development thinking and social research.

Thanks to Arif Hasan, whose Participatory Development (2010, Oxford University Press) provided much of the factual background to this piece.

Barbara Kiser is staff writer at London-based think tank the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). The views expressed here are not necessarily shared by IIED.

|