|

One of the last acts of the Labour government prior to the election was to propose changes to Britain’s war crimes legislation, to make it harder for campaigners and activists to secure arrest warrants against politically sensitive suspects. Laila Sumpton looks at what the changes could mean. One of the last acts of the Labour government prior to the election was to propose changes to Britain’s war crimes legislation, to make it harder for campaigners and activists to secure arrest warrants against politically sensitive suspects. Laila Sumpton looks at what the changes could mean.

In recent years, magistrates have granted a number of separate arrest warrants for Israeli officials visiting the UK after applications from private prosecutors, often human rights lawyers, under the principle known as universal jurisdiction.

The principle allows war crimes to be prosecuted anywhere in the world, regardless of where they were committed.

Following a private prosecutor’s request for an arrest warrant for the former Israeli Foreign Minister Tzivi Lipni, the British government apologised to Israel and vowed to change the law to make such warrants harder to secure.

The proposal

Accordingly, the Ministry of Justice published proposals in March to restrict the right to initiate proceedings under the principle known as universal jurisdiction to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

Even under the government’s proposals, certain things won’t change. Regardless of whether it was a private prosecutor or the police who initiated proceedings, it is up to the CPS and the Attorney General to decide whether to actually prosecute a suspect – and this will remain so under the proposed reforms.

Crucially, this decision is currently based on whether the authorities believe a prosecution is in the “public interest” – and the potential impact on relations with foreign governments can form a part of this judgement. The proposed reforms will not alter this.

What would change is that private prosecutors will not be able to secure arrest warrants from magistrates. Instead, the Ministry of Justice suggests that private prosecutors should submit their prima facie evidence to the War Crimes Unit in the Special Operations Department of the Metropolitan Police (SO15), rather than directly to a judge.

Nick Donovan of the Aegis Trust said he was confident that “SO15 would assess the cases and would very quickly liaise with the CPS”. This might work when the suspect is resident in the UK, but Geraldine Matiog of Human Rights Watch warned that the proposals would slow down the process, as private prosecutions are only used in cases where the person is passing through the UK and not a long-term resident.

Political will hunting

Paul Troop, of Lawyers for Palestinian Human Rights, has worked on a number of the universal jurisdiction cases that have brought a strong reaction from the Israeli government. He was sceptical about the CPS’ level of interest in war crimes cases, even when suspects are resident in the UK: “It’s clear from our experience that there’s very little expertise in these cases and very little interest in prosecuting them, and very little capacity as well.”

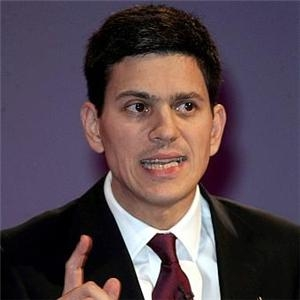

For its part, the Ministry of Justice argued in its proposal that it has the “powers and expertise to undertake [war crimes prosecutions] successfully”. David Miliband also defended the proposed changes to The Samosa: “The system we are proposing is not closed to private engagement, it’s an important part of our system, that as well as government keeping its eyes and ears open about any war criminals.” For its part, the Ministry of Justice argued in its proposal that it has the “powers and expertise to undertake [war crimes prosecutions] successfully”. David Miliband also defended the proposed changes to The Samosa: “The system we are proposing is not closed to private engagement, it’s an important part of our system, that as well as government keeping its eyes and ears open about any war criminals.”

However, since 2005 the UK Border Agency has referred 51 cases to the Metropolitan Police, none of which have resulted in an arrest or prosecution. The “eyes and ears” may be open, but the mouth isn’t talking.

Critics of the current system say that private prosecutions for war crimes are merely political. “What is not sensible,” Miliband explained, “is the anomaly that allows someone to be arrested even when there is no chance of them being prosecuted, and that's what we have proposed to remedy.”

But Troop argued that the CPS’ reluctance to prosecute showed it was they who were becoming increasingly political, whilst the claim that “anyone can go to a magistrate, inform them of a suspicion and get an arrest warrant and the judges hand them out like candy, is utterly ridiculous. In every single case the judge has discretion and does not easily issue a warrant.”

Human Rights Watch’s Geraldine Matiog added that private prosecution acted as a safety net so that the public can act when the government cannot or does not.

The day the system worked

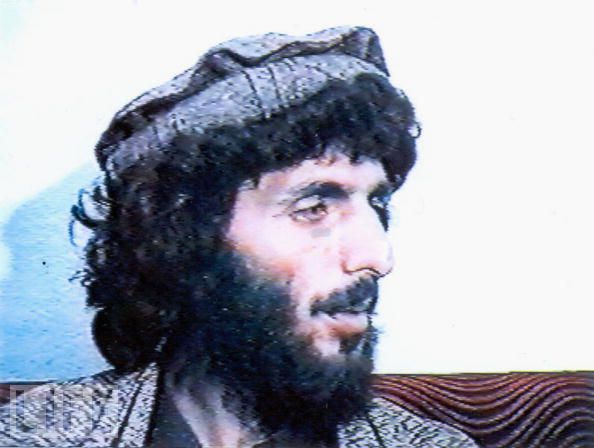

The government points to Britain’s prosecution of Afghan war criminal Faryadi Zardad in 2005 as evidence of its commitment to bringing suspects to justice.

Miliband said: “The British government takes its responsibility with respects to war crimes very seriously. We were the first country in the world to use war crimes legislation in 2005 against an Afghan warlord, so the proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

But would this prosecution have been possible under the new proposals? Matiog said that SO15 was “built up” to deal with the Zardad case. Normally, SO15’s War Crimes Unit only has two permanent officers. “When you know that the SO15 unit only has two officers on a permanent basis, you know that there is only so much they can do,” said Matiog.

By comparison, she said the Netherlands has the world’s largest war crimes unit, with 28 officers and four full-time prosecutors. Denmark has 15 staff, whilst Belgium, Norway and Germany have about eight staff in their units with three or four prosecutors.

There are doubts whether SO15, whose budget is disproportionately split between the Counter Terrorist Unit and the Crimes Against Humanity Unit, will be able to cope with extra casework. Nick Donovan from the Aegis Trust warned that the CPS and SO15’s workload would increase with the end of private prosecutions and the backdating of the War Crimes Act to 1991.

“We are urging the CPS to go back through their files and review previous cases, where we couldn’t turn around with universal jurisdiction at the time,” said Donovan.

Despite growing calls for a separate, specialised and well-funded War Crimes Unit outside SO15, there is little evidence this is being considered. Miliband told The Samosa that he had seen no evidence that SO15’s existing War Crimes Unit was underfunded.

Muddy waters

How these potential changes might work remains unclear, with a CPS spokesperson admitting “we won’t know how this is going to work until they tell us it’s going to”.

Britain’s general election may have an impact on whether the proposals ever make it across the line, but while the Liberal Democrats are sceptical about changing the law, the Conservatives are firmly in favour of restricting the use of universal jurisdiction – so a new government is unlikely to significantly alter Labour’s approach.

“I guess the optimist side of me is hoping that the issue will die, as it died in 2005 [when it was last raised],” said Matiog, “but it really depends on the government of Israel and whether they are going to keep up pressure on the UK.” |