|

Through sixty years of conflict, three full-blown wars, and twenty years of armed insurgency, the Kashmir Question is no closer to an answer – too low on the agendas of India and Pakistan to bring a concerted effort at resolution, but too high for them to just shake hands and leave the conflict in the past. So what role, if any, should their old colonial master play? Laila Sumpton reports. Through sixty years of conflict, three full-blown wars, and twenty years of armed insurgency, the Kashmir Question is no closer to an answer – too low on the agendas of India and Pakistan to bring a concerted effort at resolution, but too high for them to just shake hands and leave the conflict in the past. So what role, if any, should their old colonial master play? Laila Sumpton reports.

Some British MPs continue to campaign for Kashmiri self-determination, much to India’s displeasure and Pakistan’s delight, although sceptics see ‘self-determination’ – as distinct from ‘independence’ – as just a way of enabling Kashmir to be acceded to Pakistan.

Paul Rowen, the Liberal Democrat MP for Rochdale, is joint chair of Britain’s All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Kashmir, and will be defending a marginal seat with a significant Kashmiri population at next month’s election. At a meeting held by the group last month, he described Britain as the “grandfather” of India and Pakistan, who needs to chide its grandkids into dialogue.

Meanwhile, veteran Labour MP Sir Gerald Kaufman recently said he would raise the issue of “our position” on both Kashmir and Gaza at a meeting with Gordon Brown, seeing Britain as a key and necessary mediator in both conflicts.

British Kashmiri groups actively encourage this role. An APPG for Kashmir meeting this January was attended by Sultan Mahmood Chaudhry, the former prime minister of Pakistani-ruled Azad Kashmir and a key voice in the UK movement for Kashmiri self-determination.

He told the meeting it was “high time Britain got involved”, while Professor Zafar Kahn of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front said that the July 7th terror attacks in London were “a result of the unresolved Kashmir issue”.

But India does not appreciate the colonial sense of responsibility that Britain is being urged to feel. Liberal Democrat peer Lord Avebury warned last month of how Robin Cook had had his “head chewed off” when he raised the subject with India while foreign secretary. His successor Jack Straw fared little better.

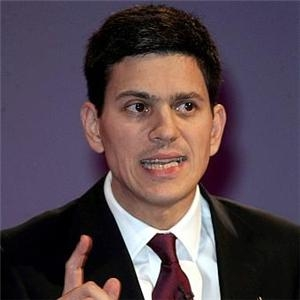

Indeed, current incumbent David Miliband’s attempt to intervene in January 2009 was deemed naive and insensitive, with Miliband depicted as Mr Bean in the Indian press – although that didn’t stop members of the APPG for Kashmir, including government minister Stephen Timms, urging him to try again.

Ali Adaalat, of the Kashmiri National Identity Campaign, said that such attempts by British foreign secretaries have “gathered publicity” but are essentially meaningless. He saw it as a campaign for a people the British government does not recognise even within the UK – pointing out there is no “Kashmiri box” on the national census. In the 2001 census, 5,000 people in Rochdale wrote “Kashmiri” on their forms.

“British foreign secretaries can’t really justify their questions because it seems that they are speaking on behalf of Pakistan rather than their Kashmiri voters,” Adaalat said.

Those MPs who campaign for Kashmiri self-determination are largely, though not exclusively, from safe Labour seats. With the election fast approaching, community groups have been encouraged to recruit their MPs to the APPG for Kashmir.

Brian Iddon, the retiring MP for Bolton South East, has been one of the most vocal campaigners. He said that Britain should veto India’s attempt to join the United Nations Security Council because of its human rights record in Indian-administered Kashmir.

But it is not just Labour MPs adding their voices. Conservative MP and junior foreign minister David Lidington told the latest APPG for Kashmir event: “Britain can’t be indifferent to India and Pakistan and must help them find a way to peace. London can’t dictate this, it must be a political settlement that the people of Kashmir find acceptable.”

Labour peer Lord Ahmed called on Britain’s Foreign Office to hold a conference on Kashmir, similar to that recently held on Afghanistan – a call echoed by many of those involved with the APPG for Kashmir. Labour peer Lord Ahmed called on Britain’s Foreign Office to hold a conference on Kashmir, similar to that recently held on Afghanistan – a call echoed by many of those involved with the APPG for Kashmir.

A Foreign Office representative told March’s APPG for Kashmir meeting that it was not proposing such a conference as the situation is “not of the same magnitude as Afghanistan or Palestine.” Foreign Office minister Mark Hendrick hinted that the absence of British and NATO troops in Kashmir was another reason for the government's public stance.

India may well view the Kashmir issue as a cover for pro-Pakistan lobbying. One commentator, who considers himself an Indian from Kashmir – rather than a Kashmiri – said there were not enough vocal Hindus in the UK to counteract the primarily Muslim self-determination movement.

He accused Kashmiri community groups of remaining silent about atrocities committed against Kashmiri Pandits.

It is also unsurprising that little is mentioned in APPG for Kashmir meetings about the escalating violence in Azad Kashmir, or the area’s reliance on Pakistan.

As for Britain’s role? David Miliband – Mr Bean to the Indian press – told British reporters on Thursday: “We support strong and improved relations between India and Pakistan, but that [Kashmir] must be a matter for India and Pakistan.”

Hardly the words of a grandfather, then.

And with Indian officials ignoring British parliamentary meetings on Kashmir, lofty discussions about self-determination might just stay within the tea rooms of Westminster.

|

What grandfather sets his children or grandchildren against each other?

There is no way that Britain can be called India's grandfather.

Britain has nothing to say in this conflict.

There can be no peace as long as Muslims want to claim India as Dar al-Islam, House of Islam. As long as they haven't achieved that, India automatically falls in Dar al-Harb, House of War. There is no peace for countries which fall in Dar al-Harb, only Hudna, which is a temporary truce, which can only last up to 10 years and is meant to regroup and strengthen their forces. How can India or anyone negotiate peace with people following such an ideology? This is simply impossible.

As much as we want world peace, sadly it cannot be achieved by negotiation.

Within Islam world peace is only possible when the whole world falls under Dar al-Islam. Because that is their ultimate goal, they call it the religion of peace, not because it is founded on peaceful principles.

For the Free World, peace is only possible if they stop Islamic Jihad once and for all. If not, the Free World can only enjoy Hudna, a short lived illusion of peace.

Britain's involvement in Afghanistan and the leeching of the conflict into areas of Pakistan means the UK is dependent to some degree on Pakistan's co-operation whilst at the same time wanting to do as much business as possible with the emerging markets in India.

Until it becomes clear either way if it is India or Pakistan that is of the greatest importance to British prosperity and / security, I suspect the government will wait and see how the situation develops or deteriorates.

Having said that, with a predicted close UK election about to take place, the threat of some well organised tactical voting by British based Kashmiris may be enough to at least move the Kashmir question further up the agenda.