|

In the second part of her look at Islam and hip-hop, Lisa Reinisch investigates the challenges facing Muslim rappers in the United States, with both the religion and the music taking root far away from the neon lights of the American Dream. In the second part of her look at Islam and hip-hop, Lisa Reinisch investigates the challenges facing Muslim rappers in the United States, with both the religion and the music taking root far away from the neon lights of the American Dream.

Hip-hop and Islam go way back – at least in terms of recent cultural history. After all, they share a hometurf in the United States: the supressed African-American community. By the time hip-hop was born in the Bronx in the late 1970s, groups like the Nation of Islam and the Five Percenters were already well established in such poor neighbourhoods. Their fusion of Islamic principles, esotericism and political activism appealed to the disempowered. As a result, many of the pioneers of hip-hop, such as Rakim Allah and Big Daddy Kane, belonged to these North American offshoots of Islam and incorporated elements of their religion into their music (Rakim even explained the meaning of the Five Percenters flag in the video to Move the Crowd).

“The first time I ever heard the name "Allah" was on a hip-hop album when I was twelve years old,“ says film director Mustafa Davis, whose new documentary Deen Tight explores how Muslim hip-hop artists approach faith and music. “Adisa Banjoko, a character in my film, says that if a Christian were to rap it’s called Christian rap. If a Jew were to rap, it’s called Jewish rap. If a Muslim raps it’s simply called hip-hop. That’s how ingrained Islam was in hip-hop from the beginning.“

Old-school hip-hop has a lot in common with Islam. Poetry, for example, is central to both cultures. Both cultivate a love of the spoken word and a reverence for wordsmiths, who can express their beliefs or deride enemies with eloquence. Even the MC battle is reminiscent of the traditions of improvised, competitive poetry found in Muslim culture. Patriarchy (including a penchant for mysogyny) and absolute loyalty to one’s family/tribe/gang are also themes that resonate in both worlds.

But while much of the early, “conscious“ hip-hop gelled reasonably well with the teachings of Islam, the same cannot be said of the music produced by gangster rappers or today’s mainstream hip-hop.

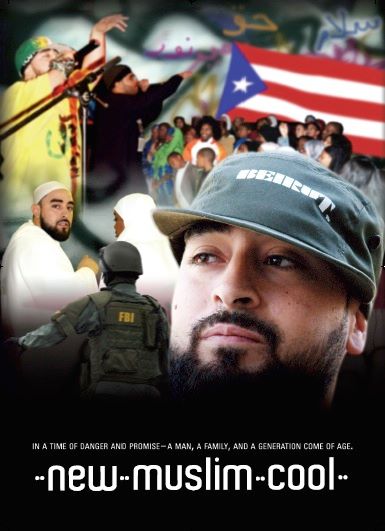

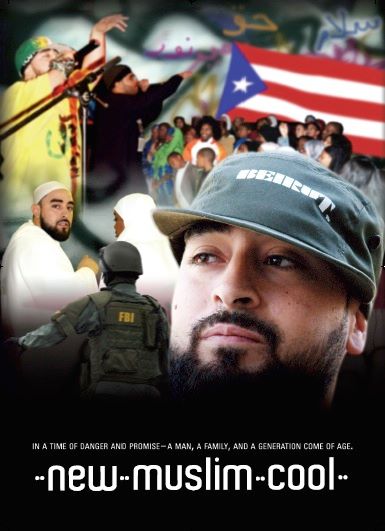

"I don't really listen to much hip-hop myself because a lot to me has become corny and plastic,“ says Hamza Perez, a Muslim artist of American-Puerto Rican descent, who became the subject of the excellent documentary New Muslim Cool after his house was raided by an FBI raid in the wake of September 11. "A lot of hip-hop fails to address the social and political struggles of our people ... like it once did.“

Mainstream hip-hop now largely stands for sex, materialism, drugs, crime and violence. As such, it has become harder to reconcile with Islamic values, making Muslim artists more vulnerable to conservative critics. Mainstream hip-hop now largely stands for sex, materialism, drugs, crime and violence. As such, it has become harder to reconcile with Islamic values, making Muslim artists more vulnerable to conservative critics.

"I respect those Muslims with those views, if they are sincere, and if I am ever doing something wrong. I would expect my brothers and sisters to want to correct me,“ says Perez. "The problem is that many Muslims just don't know the proper etiquettes of correcting people regarding Sacred Knowledge.“

The stream of cultural exchange – and criticism – goes both ways. Just as Islam appealed to disempowered African-Americans back in the 1970s, hip-hop is taking root in today’s struggling Muslim communities. As happened with Islam when it was adopted by African-Americans, when taken out of context, some of the elements of the original culture get lost.

"We see kids wearing red rags and blue rags, throwing up gang signs, without really understanding the meaning behind what they are doing,“ observes Davis. "It’s a sad phenomenon for people like us, who grew up in the West and embraced Islam as our faith. We were running from that lifestyle and to see these youth running towards it is very disheartening. It doesn't make any sense to us."

It is not just the current nature of mainstream hip-hop that is throwing the differences between the two cultures into sharper relief than ever before. Since September 11, the gulf between the US and the Middle East has widened, allowing prejudices and suspicions to prosper on both sides. For years, the situation has been exacerbated by sensationalist media coverage. Whether they want to or not, many Muslim hip-hop artists find themselves being drawn into the much-hyped rhethoric of West vs East, modernity vs Islam, Americans vs Arabs.

Many try to turn the energy behind these, sometimes imagined, conflicts into something positive. “Music allows me to bridge those gaps and show the world the new Arab, the Arab that is between both worlds and belongs to both, but doesn’t belong to either,“ says the rapper Narcicyst.

Plenty of people still subscribe to the “with us or against us“ worldview. In some sense, as long as a Palestinian can’t “just“ listen to Jewish music, it will remain difficult for Muslim artists to “just“ make hip-hop. Someone, somewhere is bound to read a whole lot more into it than they bargained for. At least for now.

|

In the second part of her look at Islam and hip-hop, Lisa Reinisch investigates the challenges facing Muslim rappers in the United States, with both the religion and the music taking root far away from the neon lights of the American Dream.

In the second part of her look at Islam and hip-hop, Lisa Reinisch investigates the challenges facing Muslim rappers in the United States, with both the religion and the music taking root far away from the neon lights of the American Dream. Mainstream hip-hop now largely stands for sex, materialism, drugs, crime and violence. As such, it has become harder to reconcile with Islamic values, making Muslim artists more vulnerable to conservative critics.

Mainstream hip-hop now largely stands for sex, materialism, drugs, crime and violence. As such, it has become harder to reconcile with Islamic values, making Muslim artists more vulnerable to conservative critics.

We mounted a very succesful six city screening of the film, and flew in Mustafa and featured spoken word artist Amir Sulaiman from the States for post screening discussions and workshops.

Arts and Islam uses informed debate and interventions to explore the issues between artistic practise, religious belief and contemporary society.

Check out our work at

http://www.artsandislam.com/