|

Anwar Akhtar visits the Whitechapel Gallery's Where Three Dreams Cross exhibition of photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and finds it says a lot not only about those countries, but also about Britain today.

The ambition in Where Three Dreams Cross is both to be admired and treated with caution. Dealing with a land mass larger than Western Europe and a population of over 1.5 billion people is a challenge, especially with the complicated family history of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. It seems bound to disappoint by missing some particular event, region or body. The ambition in Where Three Dreams Cross is both to be admired and treated with caution. Dealing with a land mass larger than Western Europe and a population of over 1.5 billion people is a challenge, especially with the complicated family history of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. It seems bound to disappoint by missing some particular event, region or body.

So the fact that it does not is testament to the skill of the photographers and curators involved. This show needs to be seen by anyone interested in South Asia – its cultures, communities, histories and diasporas.

Like many British Asians that see this show, certain photos grab you with questions and multiple meanings.

The first photos you see upon entering the gallery are of Yusuf Masih, dressed as the ancient Arab prince Mohammed Bin Qasin. An Asian man, born into a Christian family, who converted to Islam and now spends his time dressed as an ancient Arab, wandering quixotically through the heritage monuments of Pakistan – Lahore Badshah Moghul Mosque, Lahore Fort, Karachi’s Three Swords Monument and Quaid e Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s mausoleum. A mischievous mind may point to the identity issues that Pakistan, a young nation with an old history, has to grapple with.

This exhibition does great service to the cultures and communities of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, given the limitations of space and the challenges of so emotive and complex a subject. The decision not to curate by border and nation is welcome; these three countries share ancestry, tribes and bonds, something Hammad Nasar of Green Cardamom Gallery, part of the curatorial team for the show with lead curator Sunil Gupta and Kirsty Ogg, feels strongly about: “It is not an exhibition that was dictated by religion, borders or race, although those are always there. It is about a place, South Asia, and documenting its people’s photographic history.”

Partition, with all the conflict, hurt and death it came with, was not allowed to dominate the exhibition, although it too is always present in some way or form.

Hammad emphasises that this exhibition features the photography produced in these South Asian countries, not British Asian communities. He is working to use this exhibition as a catalyst for shows working with British Asian communities, which deserves support.

Anita Khemka’s photographs of Jabalpur Station in India show the exuberance and anarchy of the railway station as market, bazaar and human playground, which anyone who has been to South Asia will recognise. Farida Batool’s lenticular images of a skipping girl in the Lahore street are a joy, as is Mohammed Arif Ali’s photo of a boy in a Lahore cricket crowd, full of beauty and optimism.

Mohammed Ali Salim’s photo of construction workers, Bangladesh 1970, pre-empts the now-familiar images of cheap labour from South Asia exploited in Gulf States. His work shows their integrity, supporting families and communities with their labour.

Vicky Roy’s photo of the street children of Mumbai in what appears to be an orphanage canteen is instantly familiar, from the cinematography of Salaam Bombay and Slumdog Millionaire to many Magnum images. It has no less power for that and indicates how the welfare of so many children in South Asia is carried by the work of charities, NGOs, temples, mosques, gurdwaras, churches and thousands of volunteers amid what is often a failure of the state’s duty of care to its young citizens.

It also points to the utterly disproportionate, obscene investment in arms and weaponry that Pakistan and India’s military and political establishments are forever engaged in, and their neglect of social welfare provision. Like addicts always in need of one more hit, one more missile or submarine.

Some photos of Pakistan are compelling as they are not the Pakistan we see in our daily media coverage in Britain. Tapu Javeri’s shots of Sufi Pirs and mystics reflect the diversity of Islamic culture and heritage not just in Pakistan but across South Asia. An indigenous, pluralistic Islam, not one determined by clerics sponsored by a foreign empire, be it the USA or the Saudis.

Unsurprisingly, some of the strongest images are of the giants that defined South Asia in the 20th century. Rashid Talukder’s photo of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, one of the founding fathers of Bangladesh, returning to vast, euphoric cheering crowds in Bangladesh in 1972 after his imprisonment in Pakistan, brings to mind images of students in Tiananmen Square – the hope, optimism and humanity of a civil rights movement. Unlike Tiananmen Square, however, this civil rights movement succeeded despite the crimes committed against it.

I loved the informal photo of Jawaharlal Nehru with his grandsons Rajiv and Sanjay by Homai Vyarawalla, and another with Indira. A dynasty of huge political power, shown as a loving family rather than political players.

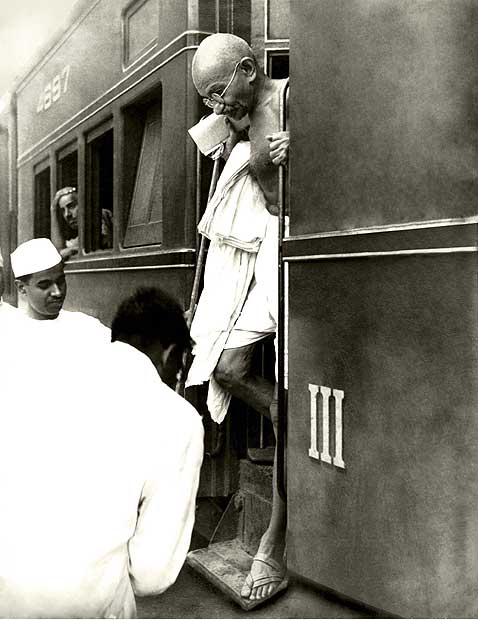

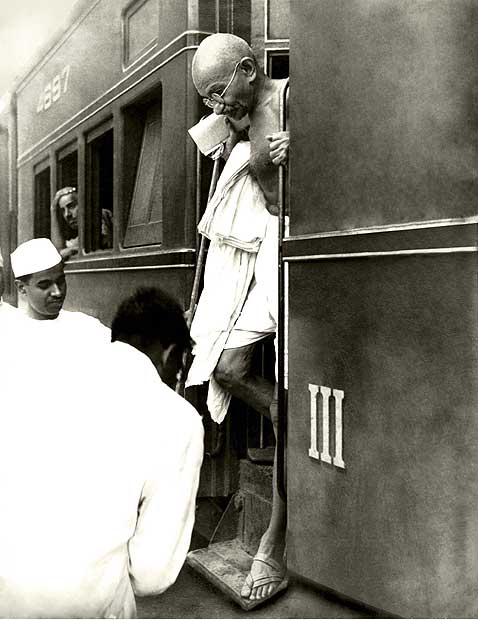

There are several shots of Mahatma Gandhi as always; he stands head and shoulders above all around, despite his tiny body. The anonymous close up, his eyes closed, almost looks like he is still here, trying get everybody to work with and not against each other. There are several shots of Mahatma Gandhi as always; he stands head and shoulders above all around, despite his tiny body. The anonymous close up, his eyes closed, almost looks like he is still here, trying get everybody to work with and not against each other.

Photos of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, are shown surrounded by other leading figures since the country’s birth and separation from India. This emphasises how devastating a loss his death in 1948 was, just a year after the founding of Pakistan. Nobody since has led or united the nation with the integrity and vision he possessed. There is wonderful photo of Benazir Bhutto at Karachi airport in 1988, laughing, happy to be home. She, perhaps, could have built on Jinnah’s vision of Pakistan as a liberal, tolerant, Islamic society that reflects the best of its people and respects all faiths, traditions and creeds. Her murder in December 2007 means it now falls to others to do so, including the photographers in this show and those of us in the diaspora.

Britain’s presence here comes not from the big box office history – the East India Company, the Bengal Famine, Empire, Kipling, Commonwealth, the many different regiments from South Asia that served the British army in both World Wars. They would be several other exhibitions in themselves.

Here you see British influence in nuances – the costumes in Hamia Vyarawalla’s photo of a party in Delhi, or Fawzan Husain and Iftikhar Dadi's cinematic stills of actors, which could belong in an Ealing film production.

The exhibition has strong images of the three countries today – modernity, urbanism, wealth, partying, glamour, conflict and poverty are all here. Asif Hazeem’s compelling photos of Hijras stand out. Pakistan’s gay and transgender communities, whose history dates back to the Moghul Emperors, recently secured overdue success in their campaign for equality and protection in society.

Anay Mann’s photos of a middle class Delhi family could be in Manhattan, Paris, or London in their domestic blissful construct. Shumon Ahmed’s multiple pictures of Bangladesh show the angst, isolation and sprawl of the metropolis in a manner reminiscent of Woody Allen’s images of New York.

What the photographers, curators and the Whitechapel Gallery have achieved here is a marker for one of the most significant exhibitions in the UK in recent years.

One depressing issue emerges. The £8.50 admission (local schoolchildren can come for free) is problematic. It would be unfair to blame the Whitechapel Gallery, who work with limited resources, have just completed a large extension into adjoining buildings, and have pulled together what is an expensive exhibition.

However given the politics of race today in Britain, and the increasing levels of racism especially towards British Muslims, this is an exhibition that should be free for all in London and also taken across the UK.

Young British Pakistanis – and this older one – would love to see the cultural context of our history and cultures, not only Pakistan’s, but our family ties in India and links with Britain that are centuries old. If you’re living in an economically and socially deprived environment, you don’t get access to the culture or history shown here. You get the English Defence League and the streets. Young British Pakistanis – and this older one – would love to see the cultural context of our history and cultures, not only Pakistan’s, but our family ties in India and links with Britain that are centuries old. If you’re living in an economically and socially deprived environment, you don’t get access to the culture or history shown here. You get the English Defence League and the streets.

This exhibition shows a history that the racists of the English Defence League and those in the right-wing press will not like, nor the tiny number of attention seeking fascists in Hizb ut-Tahrir and al-Muhajiroun. It is a history of our shared, not separate, cultures. This is an exhibition not just about Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, but the history of Britain.

We need a change of priorities from those running the Arts Council, whose focus too often is on commissioning tokenistic, culturally diverse fancy dress parades. They need to ensure a substantive show like this reaches the audiences it deserves across the UK. Wherever the English Defence League say they are going to march (read attack a British Asian community), I’d send this exhibition to the nearest gallery or town hall. Don’t hold your breath that the Arts Council will. For now though, enjoy this superb show for £8.50 at the Whitechapel Gallery in East London until 11th April.

|

The ambition in Where Three Dreams Cross is both to be admired and treated with caution. Dealing with a land mass larger than Western Europe and a population of over 1.5 billion people is a challenge, especially with the complicated family history of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. It seems bound to disappoint by missing some particular event, region or body.

The ambition in Where Three Dreams Cross is both to be admired and treated with caution. Dealing with a land mass larger than Western Europe and a population of over 1.5 billion people is a challenge, especially with the complicated family history of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. It seems bound to disappoint by missing some particular event, region or body. There are several shots of Mahatma Gandhi as always; he stands head and shoulders above all around, despite his tiny body. The anonymous close up, his eyes closed, almost looks like he is still here, trying get everybody to work with and not against each other.

There are several shots of Mahatma Gandhi as always; he stands head and shoulders above all around, despite his tiny body. The anonymous close up, his eyes closed, almost looks like he is still here, trying get everybody to work with and not against each other. Young British Pakistanis – and this older one – would love to see the cultural context of our history and cultures, not only Pakistan’s, but our family ties in India and links with Britain that are centuries old. If you’re living in an economically and socially deprived environment, you don’t get access to the culture or history shown here. You get the English Defence League and the streets.

Young British Pakistanis – and this older one – would love to see the cultural context of our history and cultures, not only Pakistan’s, but our family ties in India and links with Britain that are centuries old. If you’re living in an economically and socially deprived environment, you don’t get access to the culture or history shown here. You get the English Defence League and the streets.

I haven't been to the exhibition yet, but heard about it from a friend who is a photographer in Pakistan. I have planned to go anyway, but seeing the article above by Anwar Akhtar has made me look forward to it even more.

I have already had a little taster of what awaits, having seen a smaller, but great exhibiton of photos in Karachi, with photographs taken by some of the people in this exhibition.eg. Tupu Javeri, Ayesha Vellani.

Wouldn't it be great to have this exhibition travel to all parts of the UK --- there are so many people who love photography and are fascinated by the subcontinent. It would be great for people to see some different images from what has become the norm.

I am constantly surprised, even after 30 years living here, how limited people's knowledge is and how interested and positive they are about finding out more.

Also, it is very positive for us from the South Asian community to have the opportunity to reflect on the wealth that we have stored in our collective memories and experiences.

Is there any possiblity of this exhibition touring the country at some point? Is there anything that can be done to improve the probability of this happening?